To Break the Cycle of Poverty, don’t we first need to Remove Systemic Barriers?

In previous articles I’ve posed the question, “What is Poverty?” When visiting what we call third-world countries, I’ve been particularly taken by witnessing a level of abject poverty rarely seen in the U.S., yet often finding more smiling faces and less anxiety and depression than I see among even middle-class Americans. A totally subjective observation on my part, but one I’ve heard echoed by other travelers.

This might also be an observation and comment about poverty for which I was comfortable. Because as Tamra Ryan, the CEO of the Women’s Bean Project and author of The Third Law points out, there are a lot of us in the U.S. who are more comfortable looking at poverty in other countries than seeing it down the street from us. I’ve been one of those people, I’m afraid. It’s been easier to see the Girl Effect as investment needed in other countries, but I didn’t want to admit that much of what keeps people in poverty are the systemic barriers to getting out of it, and cultural systems for which I as a white woman in America have benefited. Ryan’s self-revelation is helping me start to see my own.

According to research by the Brookings Institute, if teens growing up in poverty finish high school, get a full-time job, and wait until age 21 to get married and have kids, nearly 75% of them will join the middle class. https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/three-simple-rules-poor-teens-should-follow-to-join-the-middle-class/

It is helpful to know the interplay of these outcomes for climbing out of poverty. This is based on a myriad of research studies that find things like – two-thirds of kids living in poverty don’t have access to books, kids with below-level reading skills are twice as likely to drop out of school, those who drop out of high school are 3.5 times more likely to be incarcerated, and 70% of incarcerated adults have low literacy rates.

While these are important success measures, I suspect that if you and I sat down next to someone living in poverty and took the time to get to know them, we’d learn they want to complete their education and hold down a full-time job. In terms of having children early, certainly it makes it more difficult to get a job and finish high school let alone graduate from college, not impossible but much more difficult. And girls born to teen parents are almost 33% more likely to become pregnant in their teens and repeat this cycle. Thankfully there are great organizations like Florence Crittenton high schools (Flo Crit) that provide the wrap around health, education and parenting services for those young ladies so that they can continue with high school and feel supported versus shamed.

Even the use of the word shamed shows my cultural bias as a European-American with its puritanical roots that judge and ostracize women who have children out of wedlock. Yet as Ryan noted, that’s not the only perspective. Many of the women employed at the Women’s Bean Project shared with Ryan that they (and their cultural mores) support having children over getting married. You’ll always love your children, but you can’t always say the same about a man. It struck me that these women were literally test driving their relationship, seeing how involved the baby daddy is before committing to marrying him. That may be a radically different perspective than I was raised with, but there’s great wisdom in it as well.

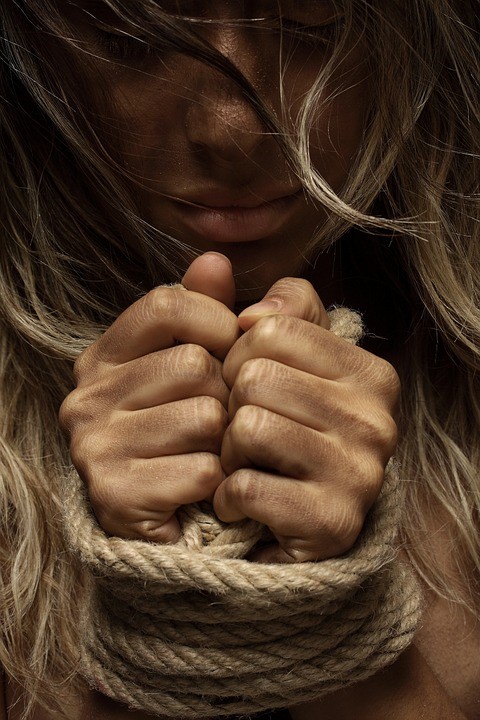

Based on Ryan’s 15+ years leading one of the first nonprofit social enterprises in the country and teaching job skills to the chronically unemployed, what drives women into poverty and/or keeps them from being employable and getting out of poverty are a trifecta of – mental health issues (perhaps born with or untreated trauma like abuse and assault) and illegal drug use, which often leads to incarceration (having a felony makes difficult to get hired). As Ryan looked at the female inmate population, she found that at least 80% of incarcerated women have at least one mental disorder, with the most frequent being drug or alcohol abuse; one-third have PTSD; and nearly 17% have been diagnosed with a major depressive disorder.

It is overwhelming to think about the interplay of these three and I don’t know where to begin with the chicken-and-egg relationship between mental health issues and addiction. So I’m going to fall back on what I do know – applying design thinking to problems (or starting with the end in mind and working backwards). If we know from the Brookings Institute that a GED and a full-time job are 2 of the 3 things that help one get out of poverty, and that incarceration is a huge barrier to employment and correlated with low literacy, could that be a trigger point for shifting the system?

According to the ACLU, nationally the number of women incarcerated in state, federal and local jails has grown 8x from 12,300 in 1980 to 182,271 by 2002. Ryan suggested much of these are nonviolent crimes tied to tougher sentencing for drug use and sales that started in response to the war on drugs.

So we have more women in prison, mostly for nonviolent offenses. What we know from the different data above suggest we must consider that many of these women are both offenders and victims. According to the Prison Policy Initiative, women are more likely than men to enter prison with a history of abuse, trauma or mental health issues, and face sexual abuse from correctional staff and other incarcerated women that further traumatizes. Women inmates are also often the primary caretaker of children (62% of incarcerated women are mothers of minors), and if there aren’t family members able to take their children they may end up in the foster system, which isn’t known for great outcomes, thereby increasing the likelihood of repeating the cycle of trauma, addiction, incarceration and poverty.

Some recommendations from the Prison Policy Initiative include:

· Take gender-responsive and trauma-informed approach – criminal justice agencies might look at alternatives to incarceration that recognize the “criminalization of women’s survival behaviors,” looks at the root issues, and does no further harm.

· Expand the use of diversion strategies and programs at each state from pre-arrest on to reduce and redirect people away from the correctional system and towards rehabilitative treatment and services especially when mental health issues are at play.

· Reclassify offenses that pose little threat to public safety or that create unnecessarily punitive sentences that criminalize poverty, like failure to pay fines and fees.

· Fund gender-responsive strategies to support women’s reentry and review collateral consequences of convictions that can be barriers to successful reentry, such as excluding access to public benefits, housing and driver’s licenses.

I’m glad to live in a state where the number of incarcerated women is falling in proportion to that of men https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/women_overtime.html. And that Colorado is piloting a wraparound approach for women and children involved in domestic violence so that they can find the safety, support and services to heal and rebuild their lives – http://roseandomcenter.org/ . Still, it’s daunting.

Some of the suggestions Ryan makes for next steps at the end of The Third Law are broader, and range from supporting sentencing reform, safe houses, and women’s nonprofits and foundations to becoming a big brother or sister, connecting addicts to resources, hiring someone trying to move off welfare or with a felony, or fostering or adopting a local child. She also referenced important solutions identify in research such as the Cliff Effect, conducted by the Women’s Foundation of Colorado.

If you have patiently read this full article, thank you, and please let me know what you think are examples of what’s working and what we could do more of. Are you part of any groups collaborating to address this? Where are places that safely and respectfully ask some of these questions of women who have reentered society after being incarcerated to ensure their experience informs this conversation? I’d also like to see this be among the follow up conversations and community dialogues that follow up to things like the Womxn’s March.

As someone whose consulting practice helps organizations improve strategic alignment, it’s impressive that Ryan and the Women’s Bean Project are so clear on their vision and their ultimate success measure would be to go out of business because they’ve solved the problem they were founded to address.

So I’ll end with Ryan’s vision and inspiring charge.

“The children of the women we employ are the future of our community. By helping their mothers change their lives, we affect their children as well as help them become contributors. It is unacceptable to allow generation after generation to become mired in addition, poverty and incarceration. For our part, the Women’s Bean Project must grow our sales and significantly increase the number of women we can employ. We must provide services so effective that we stop chronic unemployment in its tracks, reaching into the next generation and preventing the daughters from ever needing our help. I envision a day when women can break out of poverty through employment, and the social services system will enhance rather than impede this process.”